- Home

- Scott Westerfeld

The Last Days p-2 Page 9

The Last Days p-2 Read online

Page 9

One day soon, I figured, the words might actually start making sense.

The funny thing was, Alana Ray seemed to help Min the most. Her fluttering patterns wrapped around Minerva’s fury, lending it form and logic. I suspected that Alana Ray was guiding us all somehow, a paint-bucket-pounding guru in our midst.

I’d gone online a few times, trying to figure out what exactly her condition was. She twitched and tapped like she had Tourette’s, but she never swore uncontrollably. A disease called Asperger syndrome looked about right, except for those hallucinations. Maybe Minerva had called it during that first rehearsal, and Alana Ray was a little bit autistic, a word that could mean all kinds of stuff. But whatever her condition was, it seemed to give her some special vision into the bones of things.

So now that we had a drummer-sage and a demented Taj Mahal of a singer, the band only had two problems left: (1) we didn’t have a bass player, which I knew exactly how to fix, and (2) we still didn’t have a name…

“How does Crazy Versus Sane sound to you?” I asked Ellen.

“Pardon me?”

“For a band name.”

“Hmm,” she said. “I guess it makes sense; you’re going to be all New Sound, right?”

“Sort of, but better.”

She shrugged. “It’s a little bit trying-too-hard; the word crazy, I mean. Like in Catch-22. Anyone who tells you they’re crazy really isn’t. They’re just faking, or they wouldn’t know they were crazy.”

“Okay.” I frowned, remembering why hanging out with Ellen could be a drag sometimes. She had a tendency toward nonenthusiasm.

But then she smiled. “Don’t worry, Pearl. You’ll think of something. You playing guitar for them?”

“No, keyboards. We’ve got one too many guitarists already.”

“Too bad.” She pulled up an acoustic guitar case from the floor, sat it in the chair next to her. “Wouldn’t mind being in a band.”

I stared at the guitar. “What are you doing with that?”

She shrugged. “Gave up the cello.”

“What? But you were first chair last year!”

“Yeah, but cellos…” A long sigh. “They take too much infrastructure.”

“They do what?”

She sighed, rearranging the dishes on her tray as she spoke. “They need infrastructure. Most of the great cello works are written for orchestra. That’s almost a hundred musicians right there, plus all the craftsmen to build the instruments and maintain them and enough people to build a concert hall. And to pay for that, you’re talking about thousands of customers buying tickets every year, rich donors and government grants… That’s why only really big cities have orchestras.”

“Um, Ellen? You live in a really big city. You’re not planning to move to Alaska or something, are you?”

She shook her head. “No. But what if big cities don’t work anymore? What if you can’t stick that many people together without it falling apart? What if…” Ellen’s voice faded as she looked around the cafeteria once more.

I followed her gaze. The place still was only two-thirds full, with entire tables vacant and no line at all for food. It was like nobody had been scheduled for A-lunch.

It was starting to freak me out. Where the hell was everyone?

“What if the time for orchestras is over, Pearl?”

I let out a snort. “There’ve been orchestras for centuries. They’re part of… I don’t know, civilization.”

“Yeah, civilization. That’s the whole problem…” She touched the neck of the guitar case softly. “I was so sick of carrying that big cello around, like some dead body in a coffin. I just wanted something simple. Something I could play by the campfire, whether or not there’s any civilization around.”

A weird tingle went down my spine. “What happened to you this summer, Ellen?”

She looked up at me and, after a long pause, said, “My dad went away.”

“Oh. Crap.” I swallowed, remembering when my parents had divorced. “I’m really sorry. Like… he left your mom?”

Ellen shook her head. “Not right away. You see, someone bit him on the subway, and he… got different.”

“Bit him?” I thought of the rumors I’d heard, that some kind of rabies was spreading from the rats—that you could see people like Min on the streets now, hungry and wearing dark glasses.

She nodded, still stroking the guitar case’s neck. “At least I’m still on a full scholarship. So I can switch to guitar before—”

“But you’re a great cellist. You can’t give up on civilization yet. I mean, New York City’s still around.”

She nodded. “Mostly. There are still concerts and classes and baseball games going on. But it’s kind of like the Titanic: there’s really only enough lifeboats for the first-class passengers.” She scanned the room. “So when I see people not showing up, I sort of wonder if those passengers are already leaving. And then the floor’s going to start tilting, the deck chairs sliding past.”

“Um… the what?”

Ellen turned to me with narrowed eyes. “Here’s the thing, Pearl. I bet your friends are already off in Switzerland, or someplace like that.”

I shrugged. “They mostly just graduated.”

“I bet they’re in Switzerland anyway. Most people who can afford it are already gone. But my friends…” She shook her head, then shrugged. “They don’t have drivers or bodyguards, and they have to ride the subway to school. So they’re in hiding, sort of.”

“You’re here.”

“Only reason is that we live around the corner. I don’t have to ride the subway. Plus…” She smiled, touching the case in the seat next to her. “I really want to learn to play guitar.”

We talked more—about her father, about all the stuff we’d seen that summer. But my mind kept wandering to the band.

Listening to Ellen, it had occurred to me that bands like ours needed a lot of infrastructure too, as much as any symphony orchestra. To do what we did, we needed electronic instruments and microphones, mixing boards and echo boxes and stacks of amplifiers. We needed night-clubs, recording studios, record companies, cable channels that showed music videos, and fans who had CD players and electricity at home.

Crap, we needed civilization.

I couldn’t exactly see Moz and Min jamming around a campfire, after all.

What if Luz’s fairy tales were true, then, and some big struggle was coming? And what if Ellen Bromowitz had it right, and the time for orchestras was over? What if the illness that had ripped apart Nervous System was going to bring down the infrastructure that made having our kind of band even possible?

I straightened up in my chair. It was time to get moving. I had to quit patting myself on the back just because Moz was happy and Minerva was relatively noncrazy and rehearsals were going well.

We needed to become world-famous soon, while there was still that kind of world to be famous in.

14. REPLACEMENTS

— ZAHLER-

We churned out one fawesome tune after another—me, Moz, and Pearl, meeting two or three times a week at her place. After we’d used up all our old riffs, we started basing stuff on Pearl’s loopy samples, and the Mosquito didn’t even buzz about it. Ever since the band had gotten real—with a drummer, a singer, even separate amps for Moz and me—he’d finally realized that this wasn’t a competition.

What he hadn’t realized was how hot Pearl was or that she had a major crush on him.

All I could do was shake my head about that last part. The problem for Pearl was, she’d really given Moz something. She’d stripped away his shell, had shown him a way to get everything he really wanted, had helped him find a focus that he’d been too lame to discover for himself.

He was never going to forgive her for that.

Me, I still thought Pearl was hot. But for now, there was nothing I could do about it. And actually, I was happy with things the way they were. My best friend and the foolest girl in the world had finally

quit fighting, the music was fexcellent, and Pearl loved the band, which meant she wasn’t going anywhere without me tagging along.

It was all going so good, I should have known something was about to explode.

We were working on the B section of one of the new tunes, called “A Million Stimuli to Go.” It was totally complicated, and no matter how hard I tried, I just couldn’t play it. Moz kept showing me how on his Strat, but for some reason it didn’t work on my fingers.

At least, it didn’t until Pearl jumped in. She swept aside the CD cases and a harmonica scattered across her bed and sat down next to me. Unhooking the strap of my guitar, she pulled it over into her lap.

“Let me, Zahler,” she said.

Then, like it was no big deal, she started playing the part.

Normally, sitting that close to her would have been pretty fool. But at that moment I was too dumbfounded to appreciate it.

“See?” she said, her fingers practically smoking as they cruised across the strings. “You’ve just got to use your pinky on that last bit.”

Moz laughed. “He hates using his pinky. Says it’s his retarded finger.”

I didn’t say anything right then, just watched her play, nodding like a moron. She was dead on about how to make the part work, and now that I could see it from behind the strings, it didn’t even look that hard. When Pearl handed me back my guitar, I managed to get it right the first time.

She stood up and went back to her keyboards, tweaking her stacks while I ran through it a dozen more times, pushing the riff deep into my brain.

I didn’t say anything more about it till later, when it was just me and the Mosquito.

“Moz, did you see what happened back there?”

We were wandering through late-night Chinatown, surrounded by the clatter of restaurant kitchens. The thick sweat of fry-cooking rolled along the narrow streets, and the metal doors of fish markets were rumbling down, the briny smell of guts lingering in the air.

It was pretty quiet at night since the pedestrian curfew had been imposed. Moz and I always ignored the curfew, though, so it was like we owned the city.

“See what?” Moz twisted his body to peer down the alley we’d just passed.

“No, not down there.” Since that day with my dogs, I didn’t even glance into alleys anymore. “Back at Pearl’s. When she showed me that riff.” My hands lifted into guitar position, fingers fluttering. The moves were in me now, too late to save me from humiliation.

“Oh, the one you had trouble with? What about it?”

“Did you see how Pearl just did it?”

He frowned, his own fingers tracing the pattern. “That’s how it’s supposed to be played.”

I groaned. “No, Moz, not how she played it. That she played it, when it was driving me nuts!”

“Oh,” he said, then waited as a garbage truck steamed past, squeaking and groaning. For some reason, there were six guys hanging onto the back, instead of the usual two or three. They watched us warily as the truck rumbled away. “Yeah, she’s pretty good. You didn’t know that?”

“Hell, no. When did that happen?”

“A long time before we met her.” He laughed. “You never noticed how her hand moves when she calls out chords?” His left hand twitched in the air. “And I told you how she spotted the Strat, same as me.”

“But—”

“And that stuff in her room: the flute, the harmonicas, the hand drums. She plays it all, Zahler.”

I frowned. It was true, there were a lot of instruments lying around at Pearl’s. And sometimes she’d pull one down and play something on it, just for a joke. “I never noticed any guitars, though.”

He shrugged. “She keeps them under the bed. I thought you knew.”

I looked down and swung my boot at the fire hydrant squatting on the curb, catching it hard in one of its little spouty things. It clanked and I hopped back, remembering I didn’t mess with hydrants anymore. “That doesn’t bug you?”

“Bug me? I don’t care if she keeps them in the attic, as long as I get to play the Strat.”

“Not that. Doesn’t it bug you that I’m supposed to be our guitarist, and I don’t even play guitar as well as our keyboard player?”

“So? She’s a musical genius.”

I groaned. Sometimes the Mosquito could be spectacularly retarded. “Well, doesn’t that sort of imply that the ‘musical genius’ should be our second guitarist, and not me?”

He stopped, turned to face me. “But Zahler, that won’t help. You don’t play keyboards at all.”

“Ahhh! That’s not what I mean!”

Moz sighed, put his hands up. “Look, Zahler, I know she plays guitar better than you. And she understands the Big Riff better than I do, just like she does most music. She probably drums better than a lot of drummers—maybe not Alana Ray, though. But like I said, she’s a musical genius. Don’t worry. She and I were talking about you, and Pearl’s already got a plan.”

“Talking about me? A plan?”

“Of course. Pearl’s always got a plan—that’s why she’s the boss.” He smiled. “I got over it, why can’t you?”

“Why can’t I get over it?” I stood there, breathing hard, hands flexing, looking to grab something by the throat and choke it. “You weren’t over jack until a couple of weeks ago! And that’s only because you think that weird junkie friend of hers is hot!”

He stared at me, eyes wide, and I glared back at him. It was one of those things I hadn’t known until I’d blurted it out. But now I could see that it was totally true. The only reason Moz had been so fool lately was that Minerva had clicked the reset button on his brain.

I’d already told Moz what I thought of her. She was a junkie, or an ex-junkie, or a soon-to-be junkie, and was bad news. Even before she’d freaked out at Alana Ray during that first rehearsal, the whole dark glasses and trippy singing had been totally paranormal.

I’m not saying she wasn’t a good singer, just that I like my songs with words. And I like my skinny, pale chicks with veiny arms as far away as possible.

“Min’s not a junkie,” he said.

“Oh, yeah? How do you know?”

He spread his hands. “Well, how do you know she is?”

“Listen, I don’t know what she is.” I slitted my eyes. “All I know is that it’s something that they only let out for two hours a week! That’s why we rehearse early Sunday morning, right? And why those two run back to Brooklyn? Because visiting hours are over?”

Moz frowned. “Yeah, I don’t really know what that’s about.” He turned away and started walking again, like I hadn’t just been yelling at him. “I think Pearl likes to keep Minerva to herself. They’ve been friends since they were little kids, and Min’s kind of… fragile.”

I snorted. Junkies might be easy to knock down, but they’re never fragile. They have souls like old leather shoes studded with steel, and they’re about as much good as friends.

From the fish store across the street, a big Asian guy was eyeing us, a baseball bat in one hand. When I waved and smiled, he nodded and went back to tossing out bucketfuls of used ice, spreading them across the asphalt to let them melt. The icy splinters glittered in the streetlights, and I walked over to crush some under my feet.

Stupid Pearl. Stupid Moz. Stupid guitar.

Against the street, the ice looked black. People said that if you got black water into the freezer fast enough, it would freeze up instead of evaporating, and you’d have black ice. Of course, they never said why you’d want anything like that in your fridge. When I went over to Moz’s, I still crossed the street so I didn’t get too close to that hydrant, even though it had one of those special caps on it now to keep kids out.

“There’s something I should tell you about, though.” Moz’s boots crunched through the ice behind me. “But you can’t tell anyone else.”

“Great,” I murmured, smashing more ice. “Just what this band needs, more secrets.” Moz still hadn’t told Pearl he

was paying Alana Ray, or me where he was getting the money from. And apparently Pearl and Moz had their own secret plans for me…

“Min gave me her phone number.”

I spun toward him. He was smiling. “Dude! You do think she’s hot!”

He laughed, kicking a glittering spray of hail toward me. “Zahler, let me explain something to you. Minerva isn’t hot. She’s way past hot. She’s a fifty-thousand-volt plasma rifle. She’s a jet engine.”

I closed my eyes and groaned. When Moz started talking this way about a girl, it was all over. His obsessions were like an epic guitar solo playing in his brain, endless skittering riffs without any particular logic.

“She’s luminous. A rock star. So of course she’s a little strange.” He sighed. “But, yeah, you’re right. It might be weird with Pearl…”

When he said those last words, that’s when I probably should have tried to talk him out of it, but at that moment, I was all tangled up about the guitar thing—deeply pissed with Moz and Pearl. They could have at least told me I was a worthless doofus instead of thinking it behind my back and making plans.

I opened my eyes. “So, you’re plasma-rifle serious? Jet-engine serious?”

“Yeah, man. She’s hot.”

I shrugged. It wasn’t my fault if Moz decided to screw everything up. “When did she give you her number?”

“Sunday before last?”

“Ten days ago?” I rolled my eyes, wanting to make him feel stupid. “Don’t you think you should maybe do something about it?”

He swallowed, rocking on his feet a little. “It was kind of funny, though. She handed me her number so Pearl couldn’t see, and she told me to call at one in the morning. Exactly. She even set my watch to hers.”

“So she’s weird. We knew that, right?”

“I guess. Yeah, I should call her.” He started walking again, kind of twitchy, like Alana Ray before rehearsals.

I sighed, even more miserable now. Here I’d pushed Moz into going after a weird junkie chick, and it hadn’t even made me feel any better. I stopped next to a row of mini-Dumpsters outside a restaurant kitchen door and jumped up onto the edge of one, sitting there and pounding my boot heels against its metal side.

Uglies

Uglies Swarm

Swarm Pretties

Pretties Zeroes

Zeroes The Secret Hour

The Secret Hour Behemoth

Behemoth Peeps

Peeps Specials

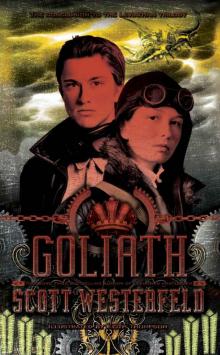

Specials Goliath

Goliath Leviathan

Leviathan Extras

Extras Shatter City

Shatter City The Risen Empire

The Risen Empire Touching Darkness

Touching Darkness The Last Days

The Last Days So Yesterday

So Yesterday The Killing of Worlds

The Killing of Worlds Afterworlds

Afterworlds Mirror's Edge

Mirror's Edge Evolution's Darling

Evolution's Darling Blue Noon m-3

Blue Noon m-3 Touching Darkness m-2

Touching Darkness m-2 Impostors

Impostors The Secret Hour m-1

The Secret Hour m-1 Leviathan 01 - Leviathan

Leviathan 01 - Leviathan Peeps p-1

Peeps p-1 Nexus

Nexus Horizon

Horizon Bogus to Bubbly

Bogus to Bubbly Goliath l-3

Goliath l-3 The Last Days p-2

The Last Days p-2 Behemoth l-2

Behemoth l-2 Stupid Perfect World

Stupid Perfect World Goliath (Leviathan Trilogy)

Goliath (Leviathan Trilogy)