- Home

- Scott Westerfeld

Peeps p-1 Page 2

Peeps p-1 Read online

Page 2

The motionless rats made me nervous. I took a plastic bag from my pocket and emptied it onto my boots. The brood parted, scenting Cornelius’s dander. My ancient cat hadn’t hunted in years, but the rats didn’t know that. Suddenly, I smelled like a predator.

Sarah clung to the bed’s spindly frame, which began to shudder. I paused to pull a Kevlar glove onto my left hand and dropped two knockout pills into its palm.

“Let me give you these. They’ll make you better.”

Sarah squinted at me, still wary, but listening. She had always forgotten to take her pills, and it had been my job to remind her. Maybe this ritual would calm her, something remembered, but not fondly enough to be an anathema. I could hear her breathing, her heart still beating as fast as it had during the chase.

She could spring at me at any moment.

I took another slow step and sat down beside her. The bed’s rusty springs made a questioning sound.

“Take these. They’re good for you.”

Sarah stared at the small white pills cupped in my palm. I felt her relax for a moment, maybe recalling what it was like to be sick—just normal sick—and have a boyfriend look after you.

I’m not as fast as a full-blown peep, or as strong, but I am pretty quick. I cupped my hand over her mouth in a flash and heard the pills snick into her dehydrated throat. Her hands gripped my shoulders, but I pressed her head back with my whole weight, letting her teeth savage the thick glove. Sarah’s black nails didn’t go for my face, and I saw swallows pulsing along her pale neck.

The pills took her down in seconds. With a metabolism as fast as ours, drugs hit right away—I feel tipsy about a minute after alcohol touches my tongue, and I damn near need an IV to keep a coffee buzz going.

“Well done, Sarah.” I let her go and saw that her eyes were still open. “You’ll be okay now, I promise.”

I pulled the glove off. The outer water-resistant layer was shredded, but her teeth hadn’t broken the Kevlar. (It has happened, though.)

My cell phone showed one lonely bar of reception, but the call went straight through. “It was her. Pick us up.”

As the phone went dark, I wondered if I should have mentioned the crumbling stairs. Oh, well. They’d figure out how to get up.

“Cal?”

I started at the sound, but her slitted eyes didn’t seem to pose a threat. “What is it, Sarah?”

“Show me again.”

“Show you what?”

She tried to speak, but a pained look crossed her face.

“You mean…” His name would hurt her if I said it. “The King?”

She nodded.

“You don’t want that. It’ll only burn you. Like the sun did.”

“But I miss him.” Her voice was fading, sleep taking her.

I swallowed, feeling something flat and heavy settle over me. “I know you do.”

Sarah knew a lot about Elvis, but she enjoyed obscure facts the most. She loved it that his mother’s middle name was Love. She searched the Web for MP3s of the B-sides of rare seventies singles. Her favorite movie was one that you’ve probably never heard of: Stay Away, Joe.

In it, Elvis is a half-Navajo bronco buster on a reservation. Sarah claimed it was the role he was born to play, because he really was part Native American. Yeah, right. His great-great-great-grandmother was Cherokee. And, like most of us, he had sixteen great-great-great-grandmothers. Not much genetic impact there. But Sarah didn’t care. She said obscure influences were the most important.

That’s a philosophy major for you.

In the movie, Elvis sells pieces of his car whenever he needs money. The doors go, then the roof, then the seats, one by one. By the end he’s riding along on an empty frame—Elvis at the steering wheel, four tires and a sputtering engine on an open road.

As the disease had settled across her, Sarah had held onto Elvis the longest. After she’d thrown out all her books and clothes, erased every photograph from her hard drive, and broken all the mirrors in her dorm bathroom, the Elvis posters still clung to her walls, crumpled and scratched from bitter blows, but hanging on. As her mind transformed, Sarah shouted more than once that she couldn’t stand the sight of me, but she never said a word against the King.

Finally, she fled, deciding to disappear into the night rather than tear down those slyly grinning faces she could no longer bear to look at.

As I waited for the transport squad, I watched her shivering on the bed and thought of Elvis clutching the steering wheel of his skeletal car.

Sarah had lost everything, shedding the pieces of her life one by one to placate the anathema, until she was left here in this dark place, clinging to a shuddering, rickety frame.

Chapter 2

TREMATODES

The natural world is jaw-droppingly horrible. Appalling, nasty, vile.

Take trematodes, for example.

Trematodes are tiny fish that live in the stomach of a bird. (How did that happen? Horribly. Just keep reading.) They lay their eggs in the bird’s stomach. One day, the bird takes a crap into a pond, and the eggs are on their way. They hatch and swim around the pond looking for a snail. These trematodes are microscopic, small enough to lay eggs in a snail’s eye, as we used to say in Texas.

Well, okay. We never said that in Texas. But trematodes actually do it. For some reason, they always choose the left eye. When the babies hatch, they eat the snail’s left eye and spread throughout its body. (Didn’t I say this would be horrible?) But they don’t kill the snail. Not right away.

First, the half-blind snail gets a gnawing feeling in the pit of its stomach and thinks it’s hungry. It starts to eat but for some reason can never get enough food. You see, when the food gets to where the snail’s stomach used to be, all that’s left down there is trematodes, getting their meals delivered. The snail can’t mate, or sleep, or enjoy life in any other snaily way. It has become a hungry robot dedicated to gathering food for its horrible little passengers.

After a while, the trematodes get bored with this and pull the plug on their poor host. They invade the snail’s antennae, making them twitch. They turn the snail’s left eye bright colors. A bird passing overhead sees this brightly colored, twitching snail and says, “Yum…”

The snail gets eaten, and the trematodes are back up in a bird’s stomach, ready to parachute into the next pond over.

Welcome to the wonderful world of parasites.

This is where I live.

One more thing, and then I promise no more horrific biology (for a few pages).

When I first read about trematodes, I always wondered why the bird would eat this twitching, oddly colored snail. Eventually, wouldn’t the birds evolve to avoid any snail with a glowing left eye? This is a nasty, trematode-infected snail, after all. Why would you eat it?

Turns out the trematodes don’t do anything unpleasant to their flying host. They’re polite guests, living quietly in the bird’s gut, not messing with its food or its left eye or anything. The bird hardly knows they’re there, just craps them out into the next pond over, like a little parasite bomb.

It’s almost like the bird and the trematodes have a deal between them. You give us a ride in your stomach, and we’ll arrange some half-blind snails for you to eat.

Isn’t cooperation a beautiful thing?

Unless, of course, you happen to be the snail…

Chapter 3

ANATHEMA

Okay, let’s clear up some myths about vampires.

First of all, you won’t see me using the V-word much. In the Night Watch, we prefer the term parasite-positives, or peeps, for short.

The main thing to remember is that there’s no magic involved. No flying. Humans don’t have hollow bones or wings—the disease doesn’t change that. No transforming into bats or rats either. It’s impossible to turn into something much smaller than yourself—where would the extra mass go?

On the other hand, I can see how people in centuries past got confused. Hordes of rats

, and sometimes bats, accompany peeps. They get infected from feasting on peep leftovers. Rodents make good “reservoirs,” which means they’re like storage containers for the disease. Rats give the parasite a place to hide in case the peep gets hunted down.

Infected rats are devoted to their peeps, tracking them by smell. The rat brood also serves as a handy food source for the peep when there aren’t humans around to hunt. (Icky, I know. But that’s nature for you.)

Back to the myths:

Parasite-positives do appear in mirrors. I mean, get real: How would the mirror know what was behind the peep?

But this legend also has a basis in fact. As the parasite takes control, peeps begin to despise the sight of their own reflections. They smash all their mirrors. But if they’re so beautiful, why do they hate their own faces?

Well, it’s all about the anathema.

The most famous example of disease mind control is rabies. When a dog becomes rabid, it has an uncontrollable urge to bite anything that moves: squirrels, other dogs, you. This is how rabies reproduces; biting spreads the virus from host to host.

A long time ago, the parasite was probably like rabies. When people got infected, they had an overpowering urge to bite other humans. So they bit them. Success!

But eventually human beings got organized in ways that dogs and squirrels can’t. We invented posses and lynch mobs, made up laws, and appointed law enforcers. As a result, the biting maniacs among us tend to have fairly short careers. The only peeps who survived were the ones who ran away and hid, sneaking back at night to feed their mania.

The parasite followed this survival strategy to the extreme. It evolved over the generations to transform the minds of its victims, finding a chemical switch among the pathways of the human brain. When that switch is thrown, we despise everything we once loved. Peeps cower when confronted with their old obsessions, despise their loved ones, and flee from any signifier of home.

Love is easy to switch to hatred, it turns out. The term for this is the anathema effect.

The anathema effect forced peeps from their medieval villages and out into the wild, where they were safe from lynch mobs. And it spread the disease geographically. Peeps moved to the next valley over, then the next country, pushed farther and farther by their hatred of everything familiar.

As cities grew, with more police and bigger lynch mobs, peeps had to adopt new strategies to stay hidden. They learned to love the night and see in the dark, until the sun itself became anathema to them.

But come on: They don’t burst into flame in daylight. They just really, really hate it.

The anathema also created some familiar vampire legends. If you grew up in Europe in the Middle Ages, chances were you were a Christian. You went to church at least twice a week, prayed three times a day, and had a crucifix hanging in every room. You made the sign of the cross every time you ate food or wished for good luck. So it’s not surprising that most peeps back then had major cruciphobia—they could actually be repelled by the sight of a cross, just like in the movies.

In the Middle Ages, the crucifix was the big anathema: Elvis and Manhattan and your boyfriend all rolled into one.

Things were so much simpler back then.

These days, we hunters have to do our homework before we go after a peep. What were their favorite foods? What music did they like? What movie stars did they have crushes on? Sure, we still find a few cases of cruciphobia, especially down in the Bible Belt, but you’re much more likely to stop peeps with an iPod full of their favorite tunes. (With certain geeky peeps, I’ve heard, the Apple logo alone does the trick.)

That’s why new peep hunters like me start with people they used to know, so we don’t have to guess what their anathemas are. Hunting the people who once loved us is as easy as it gets. Our own faces work as a reminder of their former lives. We are the anathema.

So what am I? you may be asking.

I am parasite-positive, technically a peep, but I can still listen to Kill Fee and Deathmatch, watch a sunset, or put Tabasco on scrambled eggs without howling. Through some trick of evolution, I’m partly immune, the lucky winner of the peep genetic lottery. Peeps like me are rarer than hens’ teeth: Only one in every hundred victims becomes stronger and faster, with incredible hearing and a great sense of smell, without being driven crazy by the anathema.

We’re called carriers, because we have the disease without all the symptoms. Although there is this one extra symptom that we do have: The disease makes us horny. All the time.

The parasite doesn’t want us carriers to go to waste, after all. We can still spread the disease to other humans. Like that of the maniacs, our saliva carries the parasite’s spores. But we don’t bite; we kiss, the longer and harder the better.

The parasite makes sure that I’m like the always-hungry snail, except hungry for sex. I’m constantly aroused, aware of every female in the room, every cell screaming for me to go out and shag someone!

None of which makes me wildly different from most other nineteen-year-old guys, I suppose. Except for one small fact: If I act on my urges, my unlucky lovers become monsters, like Sarah did. And this is not much fun to watch.

Dr. Rat showed up first, like she’d been waiting by the phone.

Her footsteps echoed through the ferry terminal, along with a rattling noise. I left Sarah’s side and went out to the balcony. Dr. Rat had a dozen folding cages strapped to her back, like some giant insect with old-lady hair and unsteady metal wings, ready to trap some samples of Sarah’s brood.

“Couldn’t wait, could you?” I called.

“No,” she yelled up. “It’s a big one, isn’t it?”

“Seems to be.” The brood was still behind me, quietly attending to its sleeping mistress.

She looked at the half-fallen staircase with annoyance. “Did you do that?”

“Um, sort of.”

“So how am I supposed to get up there, Kid?”

I just shrugged. I’m not a big fan of the nickname “Kid.” They all call me that at the Night Watch, just because I’m a peep hunter at nineteen, a job where the average age is about a hundred and seventy-five. All peep hunters are carriers. Only carriers are fast and strong enough to hunt down our crazy, violent cousins.

Dr. Rat’s usually pretty cool, though. She doesn’t mind her own nickname, mostly because she actually likes rats. And even though she’s about sixty and wears enough hair-spray to stick a bear to the ceiling, she plays good alternative metal and lets me rip her CDs—Kill Fee hasn’t made a dime off me since I met Dr. Rat. And mercifully, she falls well off my sexual radar, so I can actually concentrate in the Night Watch classes she teaches (Rats 101, Peep Hunting 101, and Early Plagues and Pestilence).

Like most people who work at the Night Watch, she’s not parasite-positive. She’s just a working stiff who loves her job. You have to, working at the Night Watch. The pay’s not great.

With one last look at the crumpled staircase, Dr. Rat began to set out her traps, then started laying out piles of poison.

“Isn’t there enough of that stuff around already?” I asked.

“Not like this. Something new I’m trying. It’s marked with Essence of Cal Thompson. A few swabs of your sweat on each pile and they’ll eat hearty.”

“My what?” I said. “Where’d you get my sweat?”

“From a pencil I borrowed from you in Rats 101, after that pop quiz last week. Did you know pop quizzes make you sweat, Cal?”

“Not that much!”

“Only takes a little—along with some peanut butter.”

I wiped my palms on my jacket, not sure how annoyed to be.

Rats are great smellers, gourmets of garbage. When they eat, they can detect one part of rat poison in a million. And they can smell their peeps from a mile away. Because I was Sarah’s progenitor, my familiar smell would cover the taint of poison.

I supposed it was worth having my sweat stolen. We had to kill off Sarah’s brood before it fell apart and s

cattered into the rest of Hoboken. A hungry brood that has lost its peep can be dangerous, and the parasite occasionally spreads from rats back into humans. The last thing New Jersey needed was another peep.

That’s the interesting thing about Dr. Rat: She loves rats but also loves coming up with new and exciting ways to kill them. Like I said, love and hatred aren’t that far apart.

The transport squad arrived ten minutes later. They didn’t wait for sunset, just cut the locks off the biggest set of doors and backed their garbage truck right up to them, its reverse beep echoing through the terminal to wake the dead. Garbage trucks are perfect for the transport squad. They’re like the digestive system of the modern world—no one ever thinks twice about them. They’re built like tanks and yet are completely invisible to regular people going about their regular business. And if the guys who ride on them happen to be wearing thick protective suits and rubber gloves, well, nothing funny about that, is there? Garbage is dangerous stuff, after all.

Rather than chance the ruined staircase, the transport guys reached into their truck for rope ladders with grappling hooks. They climbed up, then lowered Sarah to the ground floor in a litter. They always carry mountain-rescue gear, it turns out.

I watched the whole operation while I did my paperwork, then asked the transport boss if I could come along in the truck with Sarah.

He shook his head and said, “No rides, Kid. Anyway, the Shrink wants to see you.”

“Oh,” I said.

When the Shrink calls, you go.

By the time I got back into Manhattan, darkness had fallen.

In New York City, they grind up old glass, mix it into concrete, and make sidewalks out of it. Glassphalt looks pretty, especially if you’ve got peep eyesight. It sparkled underfoot as I walked, catching the orange glow of streetlights.

Most important, the glassphalt gave me something to look at besides the women passing by—trendy Villagers with chunky shoes and cool accessories, tourists looking around all wide-eyed and wanting to ask directions, NYU dance students in formfitting regalia. The worst thing about New York is that it’s full of beautiful women, enough to make my head start spinning with unthinkable thoughts.

Uglies

Uglies Swarm

Swarm Pretties

Pretties Zeroes

Zeroes The Secret Hour

The Secret Hour Behemoth

Behemoth Peeps

Peeps Specials

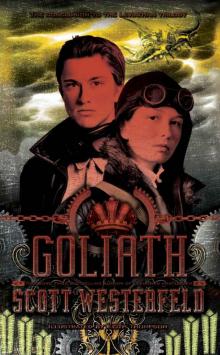

Specials Goliath

Goliath Leviathan

Leviathan Extras

Extras Shatter City

Shatter City The Risen Empire

The Risen Empire Touching Darkness

Touching Darkness The Last Days

The Last Days So Yesterday

So Yesterday The Killing of Worlds

The Killing of Worlds Afterworlds

Afterworlds Mirror's Edge

Mirror's Edge Evolution's Darling

Evolution's Darling Blue Noon m-3

Blue Noon m-3 Touching Darkness m-2

Touching Darkness m-2 Impostors

Impostors The Secret Hour m-1

The Secret Hour m-1 Leviathan 01 - Leviathan

Leviathan 01 - Leviathan Peeps p-1

Peeps p-1 Nexus

Nexus Horizon

Horizon Bogus to Bubbly

Bogus to Bubbly Goliath l-3

Goliath l-3 The Last Days p-2

The Last Days p-2 Behemoth l-2

Behemoth l-2 Stupid Perfect World

Stupid Perfect World Goliath (Leviathan Trilogy)

Goliath (Leviathan Trilogy)