- Home

- Scott Westerfeld

Peeps p-1 Page 3

Peeps p-1 Read online

Page 3

My senses were still at the pitch that hunting brings them to. I could feel the rumble of distant subway trains through my feet and hear the buzz of streetlight timers in their metal boxes. I caught the smells of perfume, body lotion, and scented shampoo.

And stared at the sparkling sidewalk.

I was more depressed than horny, though. I kept seeing Sarah on that bare and rickety bed, asking for one last glimpse of the King, however painful.

I’d always thought that once I found her, things would uncrumble a little. Life would never be completely normal again, but at least certain debts had been settled. With her in recovery, my chain of the infection had been broken.

But I still felt crappy.

The Shrink always warned me that carriers stay wracked with lifelong guilt. It’s not an uplifting thing having turned lovers into monsters. We feel bad that we haven’t turned into monsters ourselves—survivor’s guilt, that’s called. And we feel a bit stupid that we didn’t notice our own symptoms earlier. I mean, I’d been sort of wondering why the Atkins diet was giving me night vision. But that hadn’t seemed like something to worry about…

And there was the burning question: Why hadn’t I been more concerned when my one real girlfriend, two girls I’d had a few dates with, and another I’d made out with on New Year’s Eve had all gone crazy?

I’d just thought that was a New York thing.

Visiting the Shrink makes my ears pop.

She lives in the bowels of a Colonial-era town house, the original headquarters of the Night Watch, her office at the end of a long, narrow corridor. A soft but steady breeze pushes you toward her, like a phantom hand in the middle of your back. But it isn’t magic; it’s something called a negative-pressure prophylaxis, which is basically a big condom made of air. Throughout the house, a constant wind blows toward the Shrink from all directions. No stray microbes can escape from her out into the rest of the city, because all the air in the house moves toward her. After she’s breathed it, this air gets microfiltered, chlorine-gassed, and roasted at about two hundred degrees Celsius before it pops out of the town house’s always-smoking chimney. It’s the same setup they have at bioweapons factories, and at the lab in Atlanta where scientists keep smallpox virus in a locked freezer.

The Shrink actually has smallpox, she once told me. She’s a carrier, like us hunters, but she’s been alive a lot longer, even longer than the Night Mayor. Old enough to have been around before inoculations were invented, back when measles and smallpox killed more people than war. The parasite makes her immune from all that stuff, of course, but she still wound up catching it, and she carries bits and pieces of various human scourges to this day. So they keep her in a bubble.

And yes, we peeps can live a really long time.

New York’s city government goes back about three hundred and fifty years, a century and a half older than the United States of America. The Night Watch Authority may have split off from official City Hall a while back—like the peeps we hunt, we have to hide ourselves—but the Night Mayor was appointed for a lifelong term in 1687. It just so happens he’s still alive. That makes us the oldest authority in the New World, edging the Freemasons by forty-six years. Not too shabby.

The Night Mayor was around to personally watch the witch trials of the 1690s. He was here during the Revolutionary War, when the black rats who used to run the city got pushed out by the gray Norwegian ones who still do, and he was here for the attempted Illuminati takeover in 1794. We know this town.

The shelves behind the Shrink’s desk were filled with her ancient doll collection, their crumbling heads sprouting hair made from horses’ manes and hand-spun flax. They sat in the dim light wearing stiff, painted smiles. I could imagine the sticky scent left by centuries of stroking kiddie fingers. And the Shrink hadn’t bought them as antiques; she’d lifted every one from the grasp of a sleeping child, back in the days when they were new.

Now that’s a weird kink, but it beats any fetishes that would spread the disease, I suppose. Sometimes I wonder if the whole living-in-a-bubble thing is just a way to keep the Shrink’s ancient and unfulfilled desires at bay. Summer days in Manhattan, when every woman in town is wearing a tank top or a sundress, I wish they’d lock me in a bubble somewhere.

“Hey, Kid,” she said, looking up from the papers on her desk.

I frowned but could hardly complain. After being around five centuries, you can pretty much call everybody “Kid.”

I took a seat, careful to stay well behind the red line painted on the floor. If you step over it, the Shrink’s minders take everything you’re wearing and burn it, and you have to go home in these penalty clothes that are too small, like the jacket and tie they force you to wear at fancy restaurants when you show up underdressed. Everyone at the Watch remembers a carrier peep named Typhoid Mary, who wandered around too addled by the parasite to know that she was spreading typhus to everyone she slept with.

“Good evening, Doctor Prolix,” I said, careful not to raise my voice. It’s always weird talking to other carriers. The red line kept me and the Shrink about twenty feet apart, but we both had peep hearing, so it was rude to shout. Social reflexes take a long time to catch up to superpowers.

I closed my eyes, adjusting to the weird sensation of a total absence of smell. This doesn’t happen very often in New York City, and it never happens to me, except in the Shrink’s superclean office. As an almost-predator, I can smell the salt when someone’s crying, the acid tang of used AA batteries, and the mold living between the pages of an old book.

The Shrink’s reading light buzzed, set so low that its filament barely glowed, softening her features. As carriers get older, they begin to look more like full-blown peeps—wiry, wide-eyed, and gauntly beautiful. They don’t have enough flesh to get wrinkles; the parasite burns calories like running a marathon. Even after my afternoon at the diner, I was a little hungry myself.

After a few moments, she took her hands from the papers, steepled her fingers, and peered at me. “So, let me guess…”

This was how Dr. Prolix started every session, telling me what was in my own head. She wasn’t much for the so-how-does-that-make-you-feel school of head-shrinking. I noticed that her voice had the same dry timbre as Sarah’s, with a hint of dead, rustling leaves among her words.

“You have finally reached your goal,” she said. “And yet your long-sought redemption isn’t what you thought it would be.”

I had to sigh. The worst part of visiting the Shrink was being read like a book. But I decided not to make things too easy for her and just shrugged. “I don’t know. I had a long day drinking coffee and waiting for the clouds to clear. And then Sarah put up a wicked fight.”

“But the difficulty of a challenge usually makes its accomplishment more satisfying, not less.”

“Easy for you to say.” The bruises on my chest were still throbbing, and my ribs were knitting back together in an itchy way. “But it wasn’t really the fight. The messed-up thing was that Sarah recognized me. She said my name.”

Dr. Prolix’s Botoxed eyes widened even farther. “When you captured your other girlfriends, they didn’t speak to you, did they?”

“No. Just screamed when they saw my face.”

She smiled gently. “That means they loved you.”

“I doubt it. None of them knew me that well.” Other than Sarah, who I’d met before I turned contagious, every woman I’d ever started a relationship with had begun to change in a matter of weeks.

“But they must have felt something for you, or the anathema wouldn’t have taken hold.” She smiled. “You’re a very attractive boy, Cal.”

I cleared my throat. A compliment from a five-hundred-year-old is like when your aunt says you’re cute. Not helpful in any way.

“How’s that going anyway?” she added.

“What? The enforced celibacy? Just great. Loving it.”

“Did you try the rubber band trick?”

I held up my wrist. The S

hrink had suggested I wear a rubber band there and ping myself with it every time I had a sexual thought. Negative reinforcement, like swatting your dog with a rolled-up newspaper.

“Mmm. A bit raw, isn’t it?” she said.

I glanced down at my wrist, which looked like I’d been wearing a razor-wire bracelet. “Evolution versus a rubber band. Which would you bet on?”

She nodded sympathetically. “Shall we turn back to Sarah?”

“Please. At least I know she really loved me; she almost killed me.” I stretched in the chair, my still-tender ribs creaking. “Here’s the funny thing, though. She was nested upstairs, with these big-ass windows looking out over the river. You could see Manhattan perfectly.”

“What’s so strange about that, Cal?”

I glanced away from her gaze, but the blank eyes of the dolls weren’t much better. Finally, I stared at the floor, where a tiny tumbleweed of dust was being sucked toward Dr. Prolix. Inescapably.

“Sarah was in love with Manhattan. The streets, the parks, everything about it. She owned all these New York photo books, knew the histories of buildings. How could she stand to look at the skyline?” I glanced up at Dr. Prolix. “Could her anathema be, like, broken somehow?”

The Shrink’s fingers steepled again as she shook her head. “Not broken, exactly. The anathema can work in mysterious ways. My patients and the legends both report similar obsessions. I believe your generation calls it stalking.”

“Um, maybe. How do you mean?”

“The anathema creates a great hatred for beloved things. But that doesn’t mean that the love itself is entirely extinguished.”

I frowned. “But I thought that was the point. Getting you to reject your old life.”

“Yes, but the human heart is a strange vessel. Love and hatred can exist side by side.” Dr. Prolix leaned back in her chair. “You’re nineteen, Cal. Haven’t you ever known someone rejected by a lover, who, consumed by rage and jealousy, never lets go? They look on from a distance, unseen but boiling inside. The emotion never seems to tire, this hatred mixed with intense obsession, even with a kind of twisted love.”

“Uh, yeah. That would pretty much be stalking.” I nodded. “Kind of a fatal attraction thing?”

“Yes, fatal is an apt word. It happens among the undead as well.”

A little shiver went through me. Only the really old hunters use the word undead, but you have to admit it has a certain ring to it.

“There are legends,” she said, “and modern case studies in my files. Some of the undead find a balancing point between the attraction of their old obsessions and the revulsion of the anathema. They live on this knife’s edge, always pushed and pulled.”

“Hoboken,” I said softly. Or my sex life, for that matter.

We were silent for a while, and I remembered Sarah’s face after the pills had taken effect. She’d gazed at me without terror. I wondered if Sarah had ever stalked me, watching from the darkness after disappearing from my life, wanting a last glimpse before her Manhattan anathema had driven her across the river.

I cleared my throat. “Couldn’t that mean that Sarah might be more human than most peeps? After I gave her the pills, she wanted to see her Elvis doll … that is, the anathema I’d brought. She asked to see it.”

Dr. Prolix raised an eyebrow. “Cal, you aren’t fantasizing that Sarah might recover completely, are you?”

“Um … no?”

“That you might one day get back together? That you could have a lover again? One your own age, whom you couldn’t infect, because she already carries the disease?”

I swallowed and shook my head no, not wanting the lecture in Peeps 101 repeated to me: Full-blown peeps never come back.

You can whack the parasite into submission with drugs, but it’s hard to wipe it out completely. Like a tapeworm, it starts off microscopic but grows much bigger, flooding your body with different parts of itself. It wraps around your spine, creates cysts in your brain, changes your whole being to suit its purposes. Even if you could remove it surgically, the eggs can hide in your bone marrow or your brain. The symptoms can be controlled, but skip one pill, miss one shot, or just have a really upsetting bad-hair day, and you go feral all over again. Sarah could never be let loose in a normal human community.

Worse, the mental changes the parasite makes are permanent. Once those anathema switches get thrown in a peep’s brain, it’s pretty hard to convince a peep that they really, really used to love chocolate. Or, say, this guy from Texas called Cal.

“But don’t some peeps come back more than others?” I asked.

“The sad truth is, for most of those like Sarah, the struggle never ends. She may well stay this way for the rest of her life, on the edge between anathema and obsession. An uncomfortable fate.”

“Is there any way I can help?” My own words surprised me. I’d never been to the recovery hospital. All I knew about it was that it was way out in the Montana wilds, a safe distance from any cities. Recovering peeps usually don’t want their old boyfriends showing up, but maybe Sarah would be different.

“A familiar face may help her treatment, in time. But not until you deal with your own disquiet, Cal.”

I slumped in my chair. “I don’t even know what my disquiet is. Sarah freaked me out is all. I think I’m still…” I waved a hand in the air. “I just don’t feel… done yet.”

The Shrink nodded sagely. “Perhaps that’s because you aren’t done, Cal. There is, after all, one more matter to be settled. Your progenitor.”

I sighed. I’d been over all this before, with Dr. Prolix and the older hunters, and in my own head about a hundred thousand times. It never did any good.

You may have been wondering: If Sarah was my first girlfriend, where did I catch the disease?

I wish I knew.

Okay, I obviously knew how it happened, and the exact date and pretty close to the exact time. You don’t forget losing your virginity, after all.

But I didn’t actually know who it was. I mean, I got her name and everything—Morgan. Well, her first name anyway.

The big problem was, I didn’t remember where. Not a clue.

Well, one clue: “Bahamalama-Dingdong.”

It was only two days after I first got to New York, fresh off the plane from Texas, ready to start my first year at college. I already wanted to study biology, even though I’d heard that was a tough major.

Little did I know.

At that point, I could hardly find my way around the city. I got the general concept of uptown and downtown, although they didn’t really match north and south, I knew from my compass. (Don’t laugh, they’re useful.) I’m pretty sure that this all happened somewhere downtown, because the buildings weren’t quite so tall and the streets were pretty busy that night. I remember lights rippling on water at some point, so I might have been close to the Hudson. Or maybe the East River.

And I remember the Bahamalama-Dingdong. Several, in fact. They’re some kind of drink. My sense of smell wasn’t superhuman back then, but I’m pretty sure they had rum in them. Whatever they had, there was a lot of it. And something sweet too. Maybe pineapple juice, which would make the Bahamalama-Dingdong a close cousin of the Bahama Mama.

Now, the Bahama Mama can be found on Google or in cocktail books. It’s rum, pineapple juice, and a liqueur called Nassau Royale, and it is from the Bahamas. But the Bahamalama-Dingdong has much more shadowy origins. After I found out what I’d been infected with and realized who must have done it, I searched every bar I could find in the Village. But I never met a single bartender who knew how to make one. Or who’d even heard of them.

Like a certain Morgan Whatever, the Bahamalama-Dingdong had come out of the darkness, seduced me, then disappeared.

These searches didn’t evoke a single memory flashback. No hazy images of pinball machines jumped out at me, no sudden glimpses of Morgan’s long dark hair and pale skin. And, no—being a carrier doesn’t make you pale-skinned or gothy-lookin

g. Get real. Morgan was probably just some goth type who didn’t know she was about to turn into a bloodthirsty maniac.

Unless, of course, she was someone like me: a carrier. But one who got off on changing lovers into Deeps. Either way, I hadn’t seen her since.

So this is all I can remember:

There I was, sitting in a bar in New York City and thinking, Wow, I’m sitting in a bar in New York City. This thought probably runs through the heads of a lot of newly arrived freshmen who manage to get served. I was drinking a Bahamalama-Dingdong because the bar I was sitting in was “The Home of the Bahamalama-Dingdong.” It said so on a sign outside.

A pale-skinned woman with long dark hair sat beside me and said, “What the hell is that thing?”

Maybe it was the frozen banana bobbing in my drink that provoked the question. I suddenly felt a bit silly. “Well, it’s this drink that lives here. Says so on the sign out front.”

“Is it good?”

It was good, but I only shrugged. “Yeah. Kind of sweet, though.”

“Kind of girly-looking, don’t you think?”

I did think. The drink had been a vague sort of embarrassment to me since it had arrived, frozen banana bobbing to the music. But the other guys in the bar had seemed not to notice. And they were all pretty tough-looking, what with their leather chaps and all.

I pushed the banana down into the drink, but it popped back up. It wasn’t really trying to be obnoxious, but frozen bananas have a lower specific density than rum and pineapple juice, it turns out.

“I don’t know about girly,” I said. “Looks like a boy to me.”

She smiled at my accent. “Yerr not from around here, are yew?”

“Nope. I’m from Texas.” I took a sip.

“Texas? Well, hell!” She slapped me on the back. I’d already figured out in those two days that Texas is one of the “brand-name” states. Being from Texas is much cooler than being from a merely recognizable state, like Connecticut or Florida, or a huh? state, like South Dakota. Texas gets you noticed.

Uglies

Uglies Swarm

Swarm Pretties

Pretties Zeroes

Zeroes The Secret Hour

The Secret Hour Behemoth

Behemoth Peeps

Peeps Specials

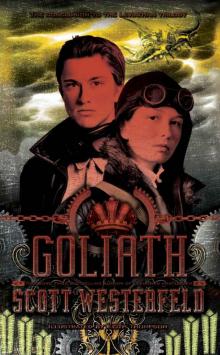

Specials Goliath

Goliath Leviathan

Leviathan Extras

Extras Shatter City

Shatter City The Risen Empire

The Risen Empire Touching Darkness

Touching Darkness The Last Days

The Last Days So Yesterday

So Yesterday The Killing of Worlds

The Killing of Worlds Afterworlds

Afterworlds Mirror's Edge

Mirror's Edge Evolution's Darling

Evolution's Darling Blue Noon m-3

Blue Noon m-3 Touching Darkness m-2

Touching Darkness m-2 Impostors

Impostors The Secret Hour m-1

The Secret Hour m-1 Leviathan 01 - Leviathan

Leviathan 01 - Leviathan Peeps p-1

Peeps p-1 Nexus

Nexus Horizon

Horizon Bogus to Bubbly

Bogus to Bubbly Goliath l-3

Goliath l-3 The Last Days p-2

The Last Days p-2 Behemoth l-2

Behemoth l-2 Stupid Perfect World

Stupid Perfect World Goliath (Leviathan Trilogy)

Goliath (Leviathan Trilogy)